One Day, to everyone’s astonishment, someone drops a match in the powder keg and everything blows up. Before the dust has settled or the blood congealed, editorials, speeches, and civil rights commissions are loud in the land, demanding to know what happened. What happened is that the Negroes wanted to be treated like [humans].

—James Baldwin, 1960

Introduction

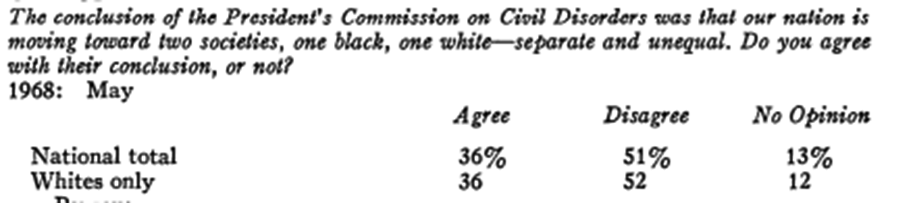

On July 27, 1967, as the greatest wave of racial uprisings to date swept across the United States, President Lyndon B. Johnson informed the nation that he was creating a special commission to answer three questions: “What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening again?” Watch President Johnson’s speech. The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, better known as the Kerner Commission, because it was chaired by Illinois Governor Otto Kerner, issued its report and answers to these questions on March 1, 1968. Whereas many Americans, including President Johnson, blamed radicals or “riot makers” for the unrest, the Commission “found no evidence that all or any of the disorders … were planned or directed by any organization or group, international, national or local.” Instead, the Commission concluded: “Pervasive discrimination and segregation in employment, education and housing,” and “the frustrations of powerlessness,” had caused the revolts. Many of the disorders, the Commission observed, were sparked by police abuses or rumors of them, to a large degree because the police had “come to symbolize white power, white racism, and white repression.” In its most controversial assertion, the Commission added that “white Americans” were “deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.” The Commission also warned that the United States was separating into two societies, “one white and one black,” and recommended implementing “programs on a scale equal to the dimension of the problems,” in other words, something akin to a domestic Marshall Plan. Copy of first part of report.

While many black leaders echoed the warnings of the Kerner Commission, with Martin Luther King, Jr. tying the “rebellions” to the “dreams of freedom” that “have been deferred” and terming riots the “language of the unheard,” President Johnson refused to endorse its findings. One of the reasons he ignored his own commission’s work was because a counter narrative or interpretation took hold among much of the public, one promoted by many politicians and pundits and lent weight by a handful of conservative scholars. Rather than blaming whites and racism, they contended that most of the rioters were composed of the “riff raff” of society who were “seeking the thrill and excitement occasioned by looting and burning.” As Harvard’s Edward Banfield put it, rioters were opportunists who looted and burned for “profit and fun,” not because they had a political agenda.

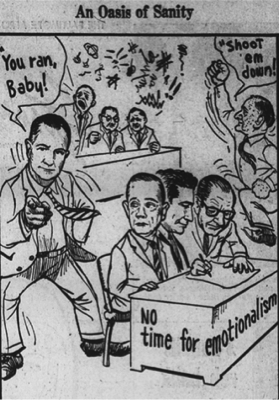

One politician who echoed Banfield’s claim was Spiro Agnew. When his hometown of Baltimore erupted into a massive riot following Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination in early April 1968, Agnew accused black radicals, most notably Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown, of inciting them. He also blamed black and white moderates for the unrest because, according to Agnew, they had enabled radicals by “cow-towing” or appeasing them. Agnew went on to lambast the Kerner Commission for its wrongheadedness. The commission blamed “everybody but the people who did it,” Agnew declared. “This masochistic group guilt for white racism pervades every facet of the Report’s reasoning. If one wanted to pinpoint one indirect cause … it would be … that lawlessness has become socially acceptable and occasionally stylish from of dissent.” Prior to 1968, Agnew had been an obscure first-term Governor from the state of Maryland with a reputation as a moderate. Afterwards, he enjoyed one of the most meteoric rises in U.S. political history, becoming Richard Nixon’s running-mate and vice president and a favorite of the burgeoning New Right. And Agnew was only one of many conservative politicians whose standing rose as they championed “law and order,” a shorthanded way of promoting a forceful repression of the rebellions and a broader backlash against an assortment of causes, from the antiwar to the women’s liberation movement, which Agnew subsequently labeled as the “radlib” menace.

As noted above, not only did the Kerner Commission find no evidence that black militants had incited riots, neither did law enforcement officials from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to the Attorney General of the United States. In the one instance where a well-known black radical, H. Rap Brown, was actually charged with inciting a riot, prosecutors ultimately dropped all charges against him, most likely because they recognized they could not prove their case in a court of law. (In the court of public opinion, most Americans remained convinced that Brown was guilty as charged.) Nor have the vast majority of scholars who studied the revolts then and since found evidence of a radical conspiracy to incite riots. They did, however, find a great deal of evidence that supported the The Kerner Commission’s conclusions that the revolts were rooted in the social and economic conditions of America’s ghettos. Indeed, a cluster of the Commission’s staffers authored an even more radical interpretation of the disorders, “The Harvest of American Racism.” It went beyond the Kerner Commission’s findings by casting the urban revolts as rational political events, aimed at fostering deep structural and political change. But this report was deemed too radical for public consumption and was kept from public view by the Commissions’ leaders.

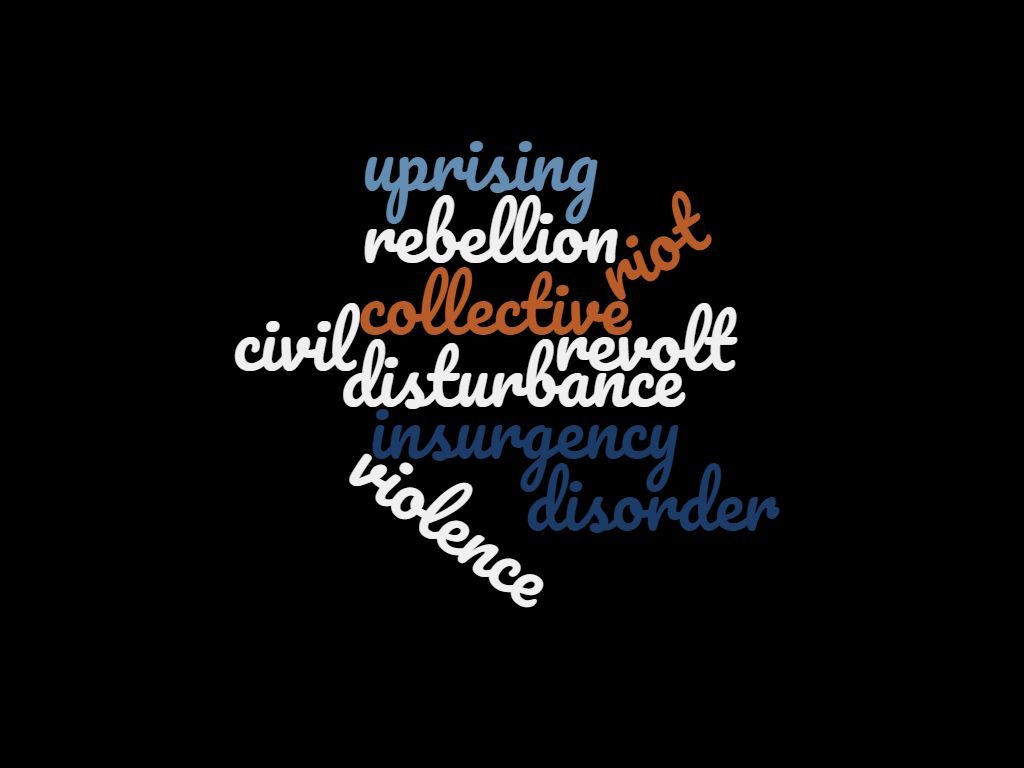

Illustrative of the somewhat different interpretations that contemporaries put forth regarding the causes of the urban revolts was the language they used to describe them. As Thomas Sugrue explains in his work Sweet Land of Liberty (2008), those who employed the term “civil disorder” or “disturbance” sought to occupy an “ostensibly neutral” stance and suggest that the nation had only experienced a temporary disruption of an otherwise tranquil state of affairs. “Riot,” in contrast, emphasized the irrationality of the mobs’ actions. “Uprisings” was the least used but perhaps most accurate expression of discontent,” adds Sugrue, “something with political content, but short of a full-fledged revolutionary act,” while “rebellion described a deliberate insurgency against an illegitimate regime, an act of political resistance with intent of destabilizing or overturning the status quo.”

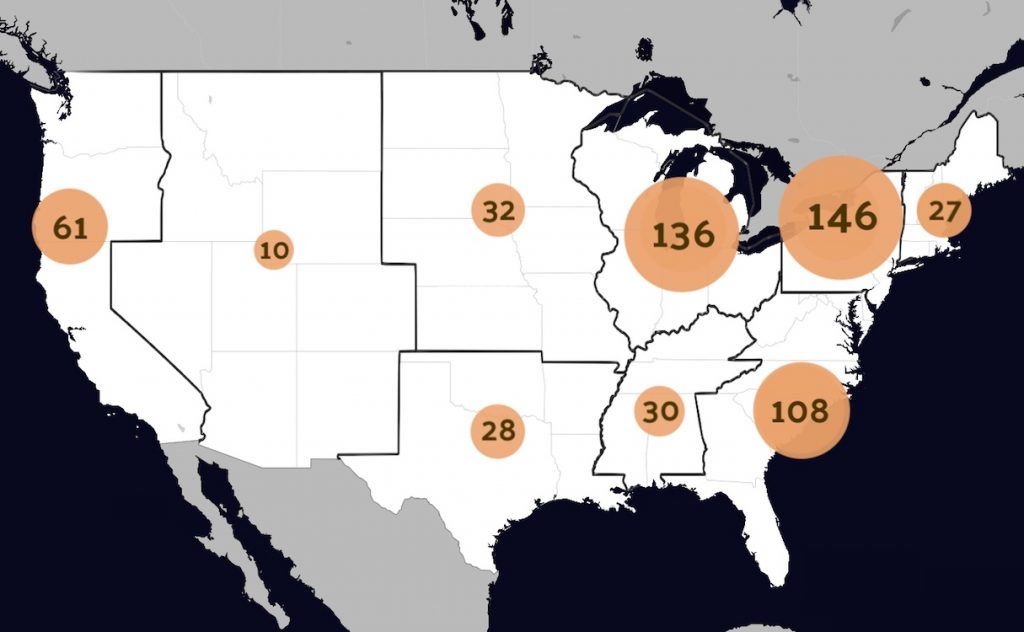

Based on my recent work, several modifications to the scholarly consensus that emerged out of the Kerner Commission’s report can be offered. First, too much of the standard interpretation of the uprisings of the 1960s has been based on the revolts that took place in Watts in 1965 and Detroit and Newark in 1967. As the map of the Great Uprising and the following charts make clear, revolts took place in all regions of the nation and in cities of all sizes. Nearly as many took place in small and mid-size cities, like Cairo, Illinois and Hartford, Connecticut, as took place in large metropolises, some with ghettos large enough to have their own names, like Harlem and Watts. Places associated with liberalism, like San Francisco, Boston, and New York, had revolts, as did backwaters of Jim Crow, such as Jackson, Mississippi, Birmingham, Alabama, and Memphis, Tennessee. Revolts took place in communities built around manufacturing, such as Patterson, New Jersey, Pontiac, Michigan, and Akron, Ohio, as well as around modern and emerging industries, such as Rochester, New York and Las Vegas Nevada. Waves of risings swept across Cleveland, Milwaukee and Chicago, in the industrial heartland, and in the fast-growing Sunbelt cities of Miami, Phoenix and Jacksonville. While it is true that most cities with over 50,000 blacks and a high percentage of those which were 25 percent black or more, experienced revolts, many cities with small black populations, both absolutely and relatively, did so as well.

| City Characteristics | 1967 | 1968 | 1969 | 1970 | 1971 | Total |

| Total Population | ||||||

| Less than 50,000 | 39 | 27 | 38 | 37 | 21 | 162 |

| 50,001-250,000 | 34 | 34 | 30 | 24 | 44 | 166 |

| 250,001 or more | 27 | 40 | 34 | 44 | 48 | 193 |

| Percent Black | ||||||

| 0 – 9.9% | 38 | 37 | 37 | 41 | 19 | 172 |

| 10 – 24.9% | 40 | 44 | 40 | 43 | 45 | 212 |

| 25% + | 21 | 19 | 22 | 16 | 36 | 114 |

Nor were the uprisings limited to urban ghettos, as testified by those that took place in the suburban communities of Plainfield, New Jersey, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, and Waukegan, Illinois. [i] Somewhat similarly, for much of the 1960s, many pundits believed that “riots” were largely clustered outside the South, especially in what has been called the rustbelt. Yet, this is not true, as the revolts were spread out across the nation, with the South Atlantic and East South Central, experiencing close to 150 revolts.

[i] The data for Tables I and II are drawn from Jane A. Baskin, Ralph G. Lewis, Joyce Hartweg Mannis and Lester W. McCullough, Jr., The Long Hot Summer? An Analysis of Summer Disorders, 1965-1971, (Waltham, MA: Lemberg Center for the Study of Violence, Brandeis University, 1972). Please note that both only include information from revolts that took place during the summers of 1967-1971.

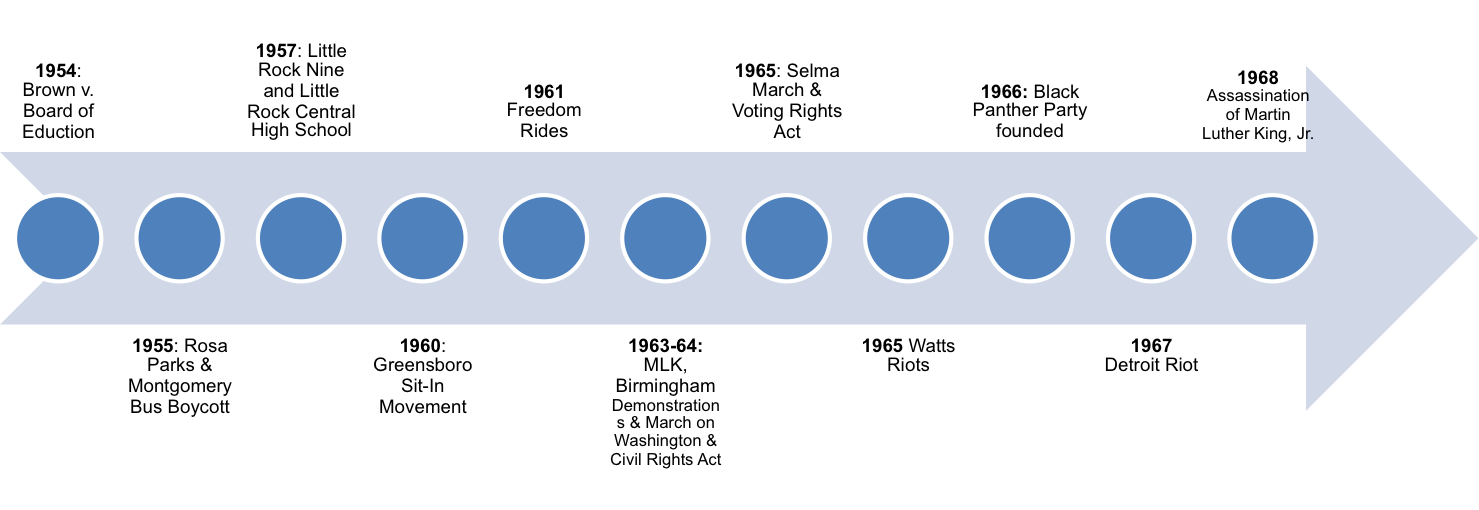

Likewise, history textbooks and popular websites too often get the chronology wrong, casting Watts (1965) as the beginning of the “urban rebellions” and Newark and Detroit (1967) as its apex, with the uprisings that followed Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination (April 1968) as an afterthought. The United States experienced racial revolts as early as 1963 in Birmingham, Alabama and Cambridge, Maryland and the revolts continued in substantial numbers after 1968. One reason many ignored or downplayed the revolts that took place prior to Watts and emphasized that they took place primarily in large cities in the north was because this view fit better with the standard framing of the civil rights movement. According to this standard telling, the civil rights movement began in the South with efforts to overturn segregation. It utilized nonviolent methods and centered on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s campaigns in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma, Alabama. Not until after Selma and the enactment of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, according to this traditional framing, did civil rights protests emerge in the North and it did so, according to the traditional narrative, with a bang—Watts—followed by a break from King’s goals of integration and nonviolence, with calls for Black Power and new waves of urban violence in America’s largest cities. The following timeline, culled from the Encyclopedia Britannica’s “Timeline of the American Civil Rights movement,” captures this traditional framing.[ii]

[ii] “Timeline of the American Civil Rights Movement,” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/list/timeline-of-the-american-civil-rights-movement

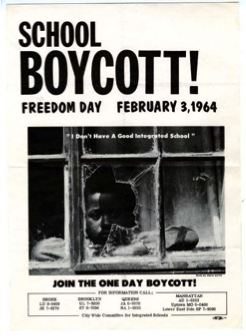

This truncation of the Great Uprising, which begins too late and ends too early, and which pays too much attention to “riots” in large cities but too little to revolts in smaller and mid-size communities across the country does not simply get the chronology and geography wrong it leads to a faulty understanding of the civil rights movement. As a good deal of recent scholarship has shown, protests against racial inequality emerged in the North alongside (not after) protests against racism in the South. Not only did Malcolm X rally activists against Jim Crow north well before his assassination in 1965, so too did many local activists in New York, Boston, Detroit, Chicago, Los Angeles and hundreds of other communities, big and small. In New York, for instance, Ella Baker, Mae Mallory, Martin Galamison and Kenneth Clarke, among others, railed against discriminatory education in local schools, not just in the deep South, as far back as the Brown decision of 1954. In response to New York City’s resistance to addressing racially discriminatory education, they organized the single largest nonviolent civil rights protest in U.S. history, a boycott of schools by over 400,000 black children in 1964. Moreover, the association between nonviolence and the South and violence and/or rebellions in the North also overlooks the degree to which many southern blacks carried weapons and practiced armed self-defense, from the Mississippi Delta to Monroe, North Carolina. In other words, self-defense and nonviolence co-existed alongside one another.

Moreover, the standard interpretation of the civil rights years as well as the Kerner Commission’s explanation for why the “disorders” took place, falls short by overlooking the years of protest against discrimination with little to no prior to the revolts. In Cambridge and Baltimore, Maryland and York, Pennsylvania, three cities I have examined intensively in The Great Uprising, activists protested against police abuse, housing and employment discrimination, a lack of recreational opportunities, and for greater political power using nonviolent means for years. But they gained only incremental or token change and in some instances one could argue things were getting worse, not better. As one black man who joined the revolt on the streets of Baltimore following Martin Luther King, explained to Father Richard Lawrence, an activist priest:

“Father you don’t understand, I know you’ve been with the demonstration and all that sort of thing. But you were born white and you really can’t totally understand. I mean I’ve done this civil rights thing too, you know it, I’ve been there; I’ve been in the marches, I’ve been in the rallies, you name it. Nobody’s listening. Murdering Dr. King was just the last straw that nobody’s listening. We can go on demonstrating as long as we want, nobody will listen. I don’t know what to try next, but maybe blood flowing in the streets is what it takes, then maybe the man will listen. Maybe not, but I’ve got nothing else left to try … I don’t care if I get killed, I’ve got two kids and I’m not going to have them come up in a world I came up in. I’m just not going to have it.”

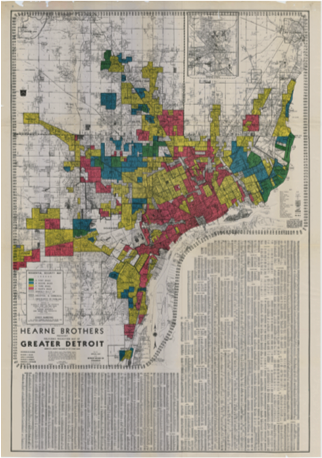

Studies of Los Angeles and Detroit by Jeanne Theoharis and Thomas Sugrue, among others, demonstrate that these well-known uprisings did not spring out of thin air. Both cities had long histories of employment, housing discrimination and police abuse and equally long histories of protest against these inequities. When Watts erupted in August 1965, California governor Pat Brown expressed his surprise, suggesting that if he had known things were bad he would have acted beforehand. Yet, as Theoharis details, blacks in Los Angeles had been protesting against unequal educational opportunities for years and the prevalence of residential segregation was well known. To make matters worse, the state government had enacted a fair housing act to discriminatory housing polices. But then, shortly before Watts erupted, the state’s voters had overturned the act, with Southern Californian white residents overwhelmingly voting in favor of maintaining a policy that allowed a homeowner to openly discriminate against a potential homebuyer simply because of the color of their skin. Moreover, as scholars have made abundantly clear in recent years, residential segregation did NOT take place because whites and black chose to live in communities with people of the same race. On the contrary, federal housing policies, initiated during the New Deal, determined where people could live through a practice known as redlining, which allowed whites to obtain mortgages to buy homes but prevented blacks from doing the same. (For more on the federal policies that helped create residential segregation across the nation see: Mapping Inequality.)

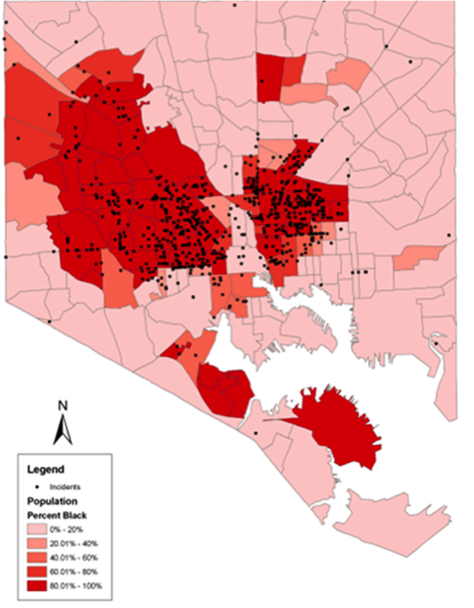

Three final misconceptions about the Great Uprising that demand attention regard the nature of the revolts and their impact. First, much of the white public feared that the revolts represented a threat to their public safety. As Black Power spokesperson Stokely Carmichael put it, “To most whites, black power seems to mean the Mau Mau are coming to the suburbs at night. The Mau Mau are coming, and the whites must stop them.” Yet, study after study of the urban revolts showed that this was not the case. Baltimore’s 1968 “Holly Week Uprising,” one of the most severe of the era illustrates this point. The vast majority of incidents took place within black neighborhoods. Not only did whites who lived in the suburbs remain secure, most public institutions, such as schools, government buildings and downtown offices, remained unscathed. Most looting and fires took place in neighborhood stores and all of those who were killed lived nearby to where they died. Along the same lines, media reports of sniper fire were vastly overstated. Careful studies of the rebellions in Newark, Detroit, and elsewhere, reveal that many if not most of the police officers and National Guardsmen who were shot during the revolts, were shot by friendly fire, by Guardsmen who were ill-prepared for urban riot duty. Not surprisingly, in 1968, after the military implemented new rules of engagement, which included keeping bullets out of the rifles of troops, fatalities went way down.

Ironically, the lack of interpersonal violence, led many to claim that the “race riots” of the 1960s were fundamentally different from those that took place earlier in the century. Scholars and the Kerner Commission characterized the “riots” of the earlier parts of the twentieth century, such as those that took place in East St. Louis and Chicago in 1919 and Detroit in 1943 as “communal” riots, whereas, they argued, those that took place in the 1960s were “commodity riots.” As most explicitly spelled out by Morris Janowitz, “commodity riots” involved attacks on property but not persons—looting and arson—while “communal riots” where characterized by interpersonal and interracial violence. Since so much of the violence in the earlier part of the century was initiated by whites—mobs and authorities—and proved far more costly to blacks than whites, this framing suggested that the “riots” of the 1960s were less justifiable, with many wondering, “why did they tear up their own neighborhoods.”

In fact, a broader examination casts doubt on claim that the revolts of the 1960s were uniformly “commodity riots.” While many of the best-known revolts, such as those in Watts, Newark, and Detroit, were dominated by looting and arson—especially if one takes reports of sniping with a grain of salt—many other revolts, especially those that took place after 1967, including many that received little attention by reporters or historians, displayed a good deal of interpersonal violence. This does not mean that blacks wantonly attacked whites. While some unprovoked attacks took place, more often than not, those blacks who used guns did so in self-defense. They fired at authorities who they did not see as their protectors, most particularly when those authorities entered their neighborhoods with force.

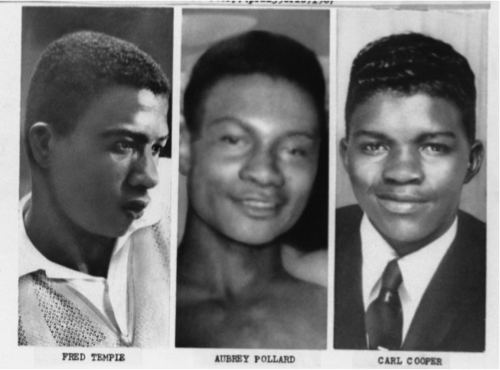

In addition, as close studies of Newark, Detroit, and elsewhere have suggested, many of the revolts went through different stages. The first stage of these “commodity riots” was in fact characterized by looting and arson. But after this first stage, the police and often state troopers, at times with the complicity of National Guardsmen, went on the offense, taking revenge with deadly force. The most famous example of this was the Algiers’ Motel incident, in which three black teens were killed by the police and nine others, including two white females, were nearly beaten to death. My case study of York, Pennsylvania’s revolt revealed a similar pattern. After a white office was shot, the largely white police force took revenge and/or encouraged and allowed white gang members to shoot at blacks, in one case fatally, with impunity.

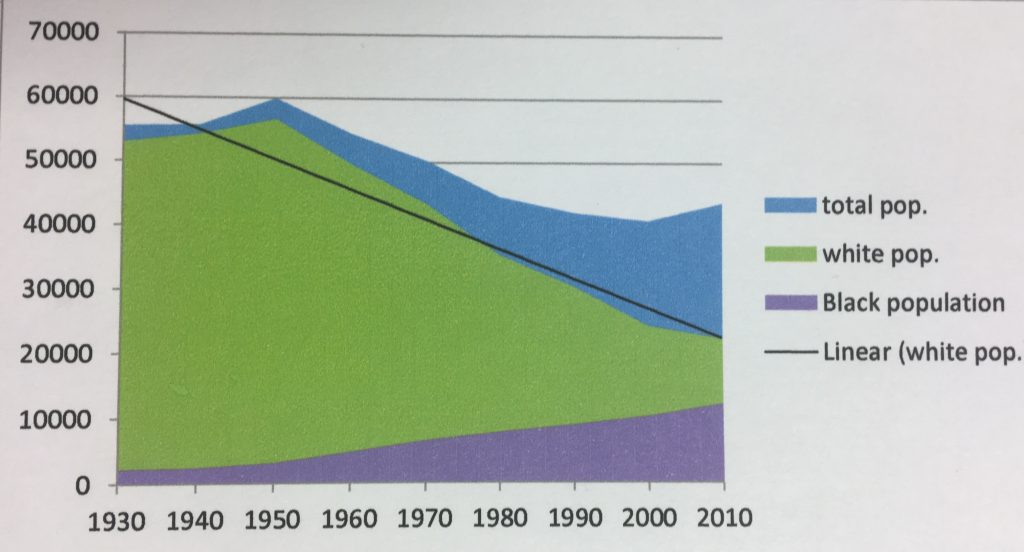

Lastly, many have misunderstood the impact or legacy of the revolts. Most commonly, the “riots” of the 1960s are characterized as a turning point, marking the moment when many of America’s cities went into decline. A survey of anniversary stories on the riots of the 1960s reveals countless people who state, matter-of-factly, that the riots led to “white flight,” meaning the decision of whites to flee to the suburbs, the demise of downtown shopping and the rise or urban crime. In fact, in city after city, white flight, or the mass movement of whites to the suburbs had begun long before the revolts took place and continued afterwards. Often, the rate of “flight” did not increase and in many instances took place in communities that did not experience revolts as well as those that did. In York, Pennsylvania, for instance, one of the three cities intensively examined in The Great Uprising, the city’s white population began to decline decades before it experienced its revolt in 1969 and the rate of “white flight” did not change afterwards (see figure below).

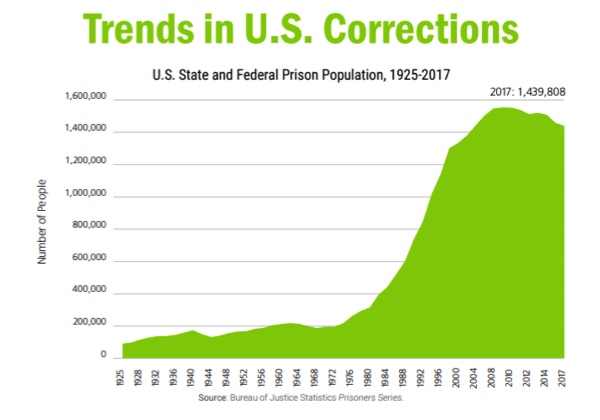

Along the same lines, downtown businesses were generally already in decline, as department stores followed their customers to the suburbs and as suburban consumers chose to shop at suburban malls and supermarket chains even, once again before the revolts took place. Likewise, urban crime, though on the rise during the 1960s, had much more to do with broad demographic trends and changing reporting standards on the part of federal, state and local authorities, than it did with the revolts. Put somewhat differently, the revolts of the 1960s were more a byproduct of the problems that beset America’s cities, from the flight of middle class taxpayers to the suburbs to the decline of downtown businesses and industries than a cause of these trends. Nevertheless, the perception that rising urban crime and the “riots” bolstered the cry for “law and order,” which paradoxically reinforced many of the problems that underlay the Great Uprising rather than producing a concerted national effort to address the great racial divide, which as the Kerner Commission noted was creating two societies, one white and one black.[iii]

[iii] The chart on incarceration rates was produced by “The Sentencing Project.” See: https://sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Trends-in-US-Corrections.pdf

At the same time, from the perspective of many black Americans, the revolts of the 1960s were not unmitigated disasters. They did not spell, as many traditional narratives of the 1960s suggest, the end of the movement for racial equality. On the contrary, in many cities, they bolstered efforts to attain political power and cultural pride. They did not undermine the welfare rights movement or efforts to unionize pubic employees, such as hospital and sanitation workers, who often were disproportionately black. Five years after the first mass wave of revolts, an estimated 10,000 black men and women gathered in Gary, Indiana, to participate in the National Black Political Convention. There, activists as diverse as Newark activist and radical Amiri Baraka, who was a driving force behind the Black convention movement, to Coretta Scott King, committed themselves to attaining greater political and economic power as well as promoting cultural pride, efforts which paid off in an explosion of black office holders and a growing black middle class.

In sum, the Great Uprising, a term neither contemporary pundits and social scientists nor historians have employed, like the Great Depression and the Great War, was one of the central developments of modern American history. It impacted millions of people, from those who took to the streets and whose businesses were looted or burned to the ground, to those who responded to the unrest, either directly or indirectly. It is my hope that this website encourages users to share their memories and to investigate the revolts that took place in their communities (and to share their findings and feelings on this site—see links to the “shoebox” and the “wall”).

See the chart below for ranking of fifty most severe revolts.[iv]

| Rank | City | Month & Year | Rank | City | Month & Year |

| 1. | Los Angeles, CA | August 1965 | 26. | Cleveland, OH | July 1968 |

| 2. | Detroit, MI | July 1967 | 27. | Akron, OH | July 1968 |

| 3. | Washington, D.C. | April 1968 | 28. | Las Vegas, NV | May 1969 |

| 4. | Newark, NJ | July 1967 | 29. | San Francisco, CA | July 1968 |

| 5. | Baltimore, MD | April 1968 | 30. | Winston-Salem, NC | November 1967 |

| 6. | Chicago, IL | April 1968 | 31. | Chattanooga, TN | May 1971 |

| 7. | Milwaukee, WI | July 1967 | 32. | Manhattan (Harlem), NY | July 1967 |

| 8. | Cleveland, OH | July 1966 | 33. | Los Angeles, CA | August 1968 |

| 9. | Pittsburgh, PA | April 1968 | 34. | Plainfield, NJ | July 1967 |

| 10. | Kansas City, MO | April 1968 | 35. | Rochester, NY | July 1964 |

| 11. | Cincinnati, OH | July 1967 | 36. | Buffalo, NY | June 1967 |

| 12. | Philadelphia, PA | August 1964 | 37. | Mobile, AL | April 1968 |

| 13. | Chicago, IL | July 1966 | 38. | Grand Rapids, MI | July 1967 |

| 14. | Newark, NJ | April 1968 | 39. | Hartford, CT | April 1968 |

| 15. | Detroit, MI | April 1968 | 40. | Ft. Lauderdale, FL | August 1969 |

| 16. | Augusta, GA | May 1970 | 41. | Toledo, OH | July 1967 |

| 17. | Cincinnati, OH | April 1968 | 42. | Nashville, TN | April 1968 |

| 18. | Miami, FL | August 1968 | 43. | San Diego, CA | July 1969 |

| 19. | Brooklyn, NY | April 1968 | 44. | Richmond, VA | April 1968 |

| 20. | Hartford, CT | September 1969 | 45. | East St. Louis, IL | September 1967 |

| 21. | Memphis, TN | April 1968 | 46. | Boston, MA | June 1967 |

| 22. | Wilmington, DE | April 1968 | 47. | Ashbury Park, NJ | July 1970 |

| 23. | Louisville, KY | May 1968 | 48. | Tampa, FL | June 1967 |

| 24. | San Francisco, CA | September 1966 | 49. | York, PA | July 1969 |

| 25. | Trenton, NJ | April 1968 | 50. | Pontiac, MI | July 1967 |

[iv] The information from this chart is drawn from a data developed by Greg Lee Carter and graciously lent to me. To learn more about the methodology he used in developing this data, see: Greg Lee Carter, “Explaining the Severity of the 1960s Black Rioting,” PhD dissertation, Columbia University, 1983 and Greg Lee Carter, “In the Narrows of the 1960s U.S. Black Rioting,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 30 (March 1986), 115-127.